The Artists on the Verge Podcast: An Accidental Narrative Research Project

As of January 2022, a year since launching the Artist on the Verge podcast (named Convo on the Verge until this month), I have completed 13 episodes, each an interview with an artist of my choice, mostly ones I have met, either in person or virtually, on my own creative journey – five composers, two improvisers, three singers, five opera and stage directors, a pop performer, a playwright, a poet, a pastor-organist (obviously, some guests represent more than one category.) These days, I converse with each artist for around an hour and cut the recording down to around 30 minutes. Each episode takes me about 13 hours to create from recording to uploading. It is what’s called a labor of love.

This process – now a monthly project – seems like one of the most important things I am doing, yet I haven’t found the right words to explain what it is that I’m doing, exactly, besides filling the interwebs with more human simulacra. It feels like I am making some kind of testament, a record of a time, and of a certain kind of person within that time. It is a time marked by seismic shifts: the first decades of ubiquitous internet use, the beginning of social media and other algorithmic sites' control over human behavior, a pandemic which has shifted what it means for people to gather the way art requires them to. It is a time when artists have instant access to the means of promoting and distributing their work, direct contact with audiences all over the world, yet have fewer opportunities to be backed by institutions, who would do that crucial work for them, than in past generations.

In the beginning of each interview, I ask my roundabout version of the same question, which I later edit out (my inarticulateness, I hope, is the same that Joan Didion claimed as her journalistic advantage): “How did you fall in love with [insert creative discipline]?” No matter how convolutedly I ask, my guests always get it - and off they go: the story of finding a record in their mother’s cabinet, the story of the old piano at their relative’s house, the story of accidentally inheriting a theater professor’s library, the story of a teacher letting them improvise on a piano after class, the story of falling in love with Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit”, the story of being a contrarian actor challenged to write a play, the story of escaping a cult with little more than a few Bibles and a harmonica. Everyone has an origin story ready to tell.

The idea for the podcast has always been to interview “indie” artists, a category I understand as indicative of something much broader than merely their source of funding. “Indie” is an ethos, a way of being, which often, though not always, goes hand in hand with founding artist-led companies and ensembles but that, in my conception, can also encompass a pop-music performer who self-publishes a novel on the music industry, or an up-and-coming theater director who doesn’t want to “become the establishment,” or a pastor who only used to go to church because he got paid to play organ and now is on a mission to point out misreadings of the Bible.

My favorite episodes are the ones where I get to speak to the artist in person – so far, that has only been two: a German composer and improviser whom I interviewed in a spare room full of boxes at the John Cage Haus in Halberstadt, Germany, where I was attending a masterclass, and a Slovak composer and improviser whom I interviewed in his kitchen in Prague. I hope to be able to do more such in-person interviews, but given where I live, in Central Europe, language has been an issue. With the Slovak composer, I dubbed over the latter part of our conversation, but that is a process that has its limitations in podcast format. I do feel called to make a record of our particular corner of the indie scene, here in post-Soviet countries, and have that as a side-project.

So, why do I do it? I still ask myself that, because it’s an impulse as mysterious to me as the sudden urge, when I was in my early teens, to become a classical singer. One of my guests recently told me that seeing himself reflected back to himself in his podcast interview was a help to his self-esteem and, yes, like so many things artists do, I make this podcast for other artists. But there is also another reason, one I realized recently at an unlikely venue.

Last week, I taught an English lesson to the Director of the Office of the Speaker of the House of the Czech Parliament in the Parliamentary building in Prague’s Old Town (yes I, like most would-be artists, have side gigs). This 35-ish assistant, high-energy and agreeable, finds himself, after the turnaround of the recent elections, in the novel position of working for a majority party, which means he must prepare for the possibility of trips abroad and English-language small talk. I turned our conversation to governmental support for the arts. He earnestly said their party has always supported the arts but, you know, they had been in the opposition until now, so couldn’t do much. And then he told me a story he seemed to be dying to tell, but wasn’t sure how he would formulate in English. So he told me in Czech. It was about going to see the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra at Rudolfínum. It was one of those events he must sometimes attend for his job - he sarcastically mentioned the receptions and the seeing-and-being-seen of it all. As he was listening to the concert, which featured Rachmaninov, a novel thought occurred to him: Each one of those instrumentalists in the orchestra has a story. They probably have the regular, middle-class life offered by an orchestral salary. “Maybe some of them take the tram home after concerts and no one recognizes them!” He decided to look at each of the members of the orchestra to remember their faces.

Several weeks later, he was at a pub and saw a frowning, unapproachable man drinking beer alone at the taps.

“You look like John Travolta,” he told him.

“Haven’t heard that one before,” said the man.

“No, you’re a Travolta, I remember you – you play with the radio orchestra.”

The man thawed. They talked about Rachmaninov.

“Silly story,” concluded the Director of the Office of the Speaker of the House and promised to tell it to me again in English, next time.

I didn’t really know how to express how I felt about what he had told me. On the one hand, his story was heartwarming, on the other, it betrayed how, to regular people - and to me even billionaires and presidents are regular people if they are not also artists – the idea that orchestral players have regular lives, that they are real people who take public transportation, necessitates an imagination few have time to indulge. The Artists on the Verge podcast deals with a different kind of artist than employed orchestral players, but it is trying to do the same thing: Look at these people. They are your neighbors. They mix the sound in your movies, publish books you read, drive your Ubers, teach your children piano, lead service at your church. And they dream.

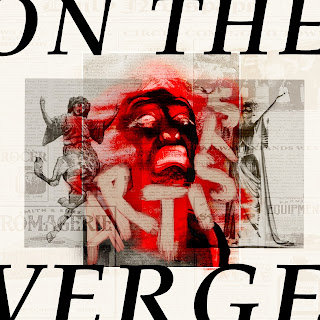

My sixteen-year-old little sister, who created the new logo for the podcast (the image for this blog post), has recently applied to the two major fine arts academies here in Prague. This was a surprise to everyone – she had always done well in school, and our mother hoped she would do something in science or diplomacy. I can’t say I am happy for my sister that she had chosen this path. There is no warning that could prepare a sixteen-year-old for what it means to be an artist, that is, an average one, not the one most often in the public eye. I know this, because nothing anyone could have said to me at that age would have discouraged or prepared me. For most, being in artist is a life of unrequited love. There is no rest, no arrival. One risks feeling – and being - useless. The only choice one has, really, is to love as best one can, that is, selflessly. Like the Slovak composer I interviewed recently said: I started being an artist when I realized I was nobody. But being nobody and being somebody and being everybody are philosophically linked, in my mind, and that is what I try to capture in my interviews – these nobodies are somebody and they are everybody. Look at their faces, listen to their voices. Think of them as the person next to you on a tram.

Comments

Post a Comment